by

In any company, small or large, clear communication between employees is critical. Everyone’s working on different things, and it’s vital that you’re able to update each other on the status of your projects.

Project management applications like Trello and Basecamp make it easier, but sometimes you still need to write a simple status report. Maybe your boss has asked you for one, maybe you’re trying to secure support or funding for your project, or maybe you just want to keep a colleague in the loop.

In this tutorial you’ll learn how to write an effective status report. They can take many forms, of course, all the way from a quick, informal email update to a formal report following a prescribed template. So what you’ll learn in this tutorial will be applicable to many different kinds of reports.

You’ll find out what you need to do to organize your key ideas and communicate them clearly, and learn about common mistakes to avoid. I’ll also give you a sample report that you can view or download, so that you can use it as a template for your own reports.

By the end, you’ll be able to write a clear, compelling status report that will help your boss or anyone else to understand exactly where you are in your project.

1. Ask Questions

It may seem strange to start by asking questions—after all, the job of a status report is to provide information, not request it. But it’s a crucial first step.

If you want your report to have maximum impact, you need to understand your audience and what their priorities are. This can help you avoid the common “laundry list” mistake, which we’ll cover in the next section, and instead focus on the things that are interesting and relevant to your intended reader.

For example, let’s say you’re reporting to your manager on the status of a new feature you’re adding to the company website. Before launching into a list of all the things you’ve achieved, you need to start by understanding your manager's expectations.

Why is the new feature important? What results are you expected to show? How much detail does your boss really need to receive? Are there particular aspects of the project that are important to her, and others she doesn’t care too much about?

She might be interested in how this new feature can improve sales, for example, but not care too much about the technology behind it. She might be seeing this as the first stage in a much larger project, or as part of a separate initiative involving other parts of the company. It’s important to understand all the background.

You probably know some of these details already, but if not, ask directly. The more clarity you can get at the beginning, the smoother the process will be.

It’s also worth asking for some guidance on what sort of length or level of detail she’s expecting, and whether there’s a particular format you should be using. Some companies have standard templates, or use special reporting software likeStatusPath or Reportify. If not, at least get a rough idea of whether you need to produce a few bullet points or a ten-page report.

When you’ve finished gathering information, it’s time to move on and start writing. We’ll start with some general points, and then go into some specifics on putting it all together.

2. Focus on Results, Not Activities

When you’re writing a status report, the natural thing to do is to think back over what you’ve done, and write it all down. Unfortunately, that’s the last thing you should be doing.

That approach leads to a dull “laundry list” of activities, many of which have no relevance to your reader. They may seem important to you, because you spent so much time on them, but your reader doesn’t need to know every step you took.

For example, if you’ve launched a new feature on the company website, you might be tempted to include everything that led up to that, all the hard work and meetings and negotiations, the technical challenges you overcame, and the legal approvals you obtained.

All of those things were important steps in completing the project, but your boss doesn’t need to know about them in any detail, and some of them may not even be worth mentioning at all.

So instead of listing tasks completed, focus on showing the results. That may require some deeper thinking. The results, after all, are more than just “launching the new website feature”. What are the wider results of that? What impact is your project having?

You may want to include statistics, for example, on how many customers have used the new feature, and what they’ve used it for. If it’s led to increased sales, or lower costs, or if it’s solved problems for customers, then definitely list all those as positive results.

3. Include the Key Elements of an Effective Status Report

Although companies may have their own formats for status reports, there are certain key elements that you should include in any effective report. Here’s a checklist for you:

Executive Summary

You don’t have to call it an executive summary, but you definitely should have a quick section right at the top, no more than two or three sentences or bullet points, summarizing the overall status of your project.

Where are you, what’s next, are you on schedule, and do you face any major issues? Imagine that your boss won’t read past this section (that may in fact be the case), and ensure that she gets all the essential information right here.

Progress Against Milestones

If you planned the project carefully to begin with, you probably broke it down into a series of individual tasks and objectives, with due dates on each of them. Your status report should contain updates on your progress in meeting those due dates. In the case of partially completed tasks, you can assign a percentage to show how close you are to completion.

Depending on the level of detail you went into in the project plan, it may not be worth listing every single task on here. Remember that you’re designing a report based on what your reader wants to know, not based on listing everything you’ve done. So perhaps just pick out certain key milestones in the project, and report your progress in meeting them.

Key Issues

Even with careful planning, most projects hit some obstacles along the way. You may be tempted to minimize them, especially if you’re reporting to someone who has a strong interest in the project’s success. But it’s vital that you disclose them as soon as possible, for two reasons:

- One of a manager’s key roles is helping to clear away obstacles. Your manager may be able to use her knowledge, connections and influence to solve a problem that could otherwise have derailed your project.

- If a project is going to go off-course, it’s far better to disclose it sooner rather than later. At an early stage, you can still work with your manager and colleagues to find a solution and meet the overall project deadline. The very last thing you want to be doing is disclosing key issues right at the end, when you’ve already missed the deadline.

Action Steps

Nobody likes to be told about problems without being offered a solution. For every issue you’ve identified, you need to outline what steps you plan to take. If you need more help, then ask for it, but you should at least have some plan of your own.

Also outline next steps for the project in general. What are the key things you’ll be working on between now and the next status update? What are the next major milestones, when do you expect to hit them, and who’s responsible for them? Give your reader an idea of what’s coming up, so that they have a clear idea of the direction the project is heading in.

4. Be Visual

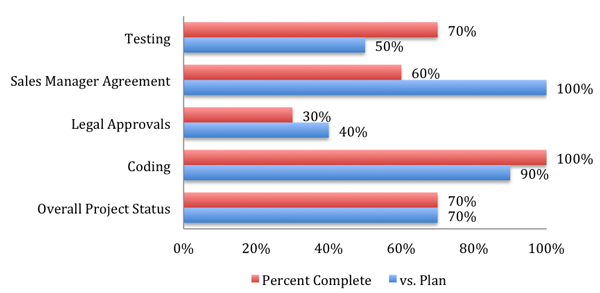

A simple chart can communicate the status of a project far more effectively than pages of text. Consider some of the following options:

- A simple traffic-light approach: Use red, green and yellow to give a quick, visual summary of the status of the overall project and its key tasks.

- Percentages: Try a simple bar chart, with a scale from 0% to 100%, and bars showing how far along you are on each task.

- A Gantt chart: This project management tool is great for showing the timeline for completion of the project. Be careful, though—very detailed Gantt charts can be tough to read if you’re not very familiar with the nitty-gritty of the project. Maybe present a simplified version.

- Issues chart: It depends on the type of project, but in some cases it may be useful to track the number of issues encountered over time, and how many have been resolved. You can use simple column or line charts for this.

Here's an example of how the percentages chart could look:

5. Keep It Short

If you’ve been told to follow a particular template or write to a particular length, then of course do that. Otherwise, the rule is to keep it as short as possible.

Put yourself in your reader’s shoes. If you’re reading a status report, you want to find out what’s happening with the project as quickly and easily as possible. You’d much rather read a cogent one-page summary than a detailed booklet telling you more than you really need to know. So if that’s what you’d like to read, then that’s what you should aim to produce.

In such a short report, of course, you won’t be able to include everything. That’s OK. If your manager wants extra information, she’ll ask for it. It’s much better for her to clearly understand the overall status of the project than to have been unable to find the essential information amid a mass of detail.

Have Stuff in Your Back Pocket

If questions do arise, you should of course be ready to answer them instantly. So along with your one-page summary report, you should prepare extra materials to answer any questions you anticipate.

Often, status reports go along with a meeting to discuss the project. If that’s the case, it provides a natural forum for answering additional questions. To ensure you’re ready, take all the information that didn’t make the cut for the report itself, and assemble it in a well-organized folder, so that you can easily access it whenever necessary.

When I worked in corporate banking, I used to call this “having stuff in my back pocket”. I’d try to anticipate any question my manager could ask, and have a chart or data point that I could whip out from my metaphorical back pocket to answer it. When the questions were asked, it made me look well prepared. Even when they weren’t, it made me feel well prepared.

If you’re sending your report by email, you could attach your “back pocket” information as an extra file, making it clear that it’s only optional, and that the essential information is contained in the report. Or alternatively you could simply say that you have more detail that you can provide if required.

6. Example Status Report Template

So now it's time to put all those elements together into a simple, clear report. Here’s how it could look:

I've attached the Microsoft Word document to this tutorial (just click in the sidebar to download it). Feel free to use it as a template, adapting it as necessary to fit your needs.

Next Steps

So now you know how to write an effective status report. You can get started, either by using my template as a starting point, or by composing your own in a format you prefer. Just remember the key points:

- Ask questions.

- Focus on results, not activities.

- Include a brief summary, a view of your progress against milestones, key issues you've encountered, and future action steps.

- Include charts or other visual elements.

- Keep it short, and have extra information in your back pocket.

.webp)